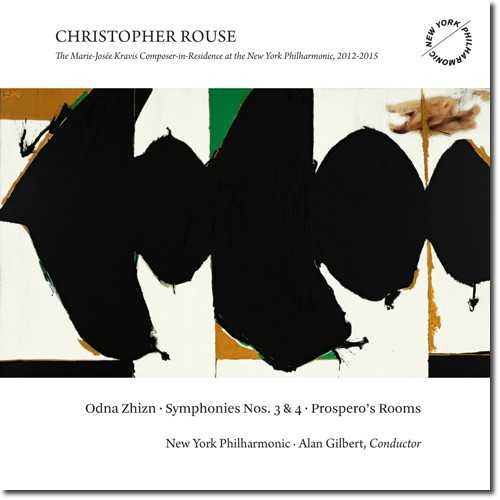

Composer: Christopher Rouse

Orchestra: New York Philharmonic Orchestra

Conductor: Alan Gilbert

Audio CD

Number of Discs: 1

Format: FLAC (tracks)

Label: Dacapo

Size: 1.4 GB

Recovery: +3%

Scan: yes

Odna Zhizn (2008) for orchestra

01. Odna Zhizn

Symphony No. 3 (2011)

02. I. Allegro

03. II. Theme

04. III. Variation 1

05. IV. Variation 2

06. V. Variation 3

07. VI. Variation 4, 5, and Theme

Symphony No. 4 (2013)

08. I. Felice

09. II. Doloroso

Prospero’s Rooms (2012) for orchestra

10. Prospero’s Rooms

Stunning Rouse From Gilbert And The New Yorkers

Conductor Alan Gilbert is no stranger to Rouse’s music as he has conducted it quite a bit through the years and has even recorded two previous recordings for the BIS label. All of these works from Rouse are newer works from him and they display a wide array of styles. Perhaps to give an idea of each work, I’ll let Mr. Rouse himself explain them:

Odna Zhizn –

“In Russian, “odna zhizn” means “one life.” This fifteen-minute work has been composed in homage to a person of Russian ancestry who is very dear to me. Her life has not been an easy one, and the struggles she has faced are reflected in the sometimes peripatetic nature of the music. While quite a few of my scores have symbolically translated various words into notes and rhythms, this process has been carried to an extreme degree in Odna Zhizn: virtually all of the music is focused on the spelling of names and other phrases, and it was an enormous challenge for me to fashion these materials into what I hoped would be a satisfying musical experience that functions both as the public portrayal of an extraordinary life as well as a private love letter.”

Symphony No. 3 –

“Over the years I’ve often toyed with the concept of “rewriting” a work composed by someone else. By this I do not mean “correcting” or “improving” it; rather, my idea has been to take some central aspect of an already composed work and consider it anew.

My third symphony is an attempt to do just this. The unusual form of Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 2 furnished the old bottle into which I have tried to pour new wine. Among Prokofiev’s symphonies this one is, I believe, of especially high caliber, though it is rarely programmed. He called it his “symphony of iron and steel,” and it is unquestionably one of his more aggressive and uncompromising scores. Cast in two movements – an opening toccata-like allegro followed by a set of variations – Prokofiev’s own architecture was in turn influenced by that of Beethoven in his final piano sonata. I thus took this structure as my own and tried to maintain Prokofiev’s own proportions between the two movements.

There is little in the way of actual quotation from Prokofiev’s symphony. However, Prokofiev’s opening repeated-note trumpet blasts also begin my symphony, though Prokofiev’s D has here been replaced by an F. There is also a direct quote at the end of my first movement: the solo percussion passage at the end of Prokofiev’s first movement has been transferred here by way of homage. As in the Russian master’s score, the music of this movement is often savage and aggressive.

The second movement of Beethoven’s sonata consists of a theme with four variations and the equivalent movement in Prokofiev’s symphony of a theme with six variations. I decided to split the difference and commit to a theme-with-five-variations form. The variations are of notably disparate character, and the musical language ranges from the dissonant and barbaric to the overtly tonal. After the statement of the theme, the bright and glittering first variation gives way to a highly romantic variation scored for strings and harps only. The third variation is moderate in tempo and mood, but the short fourth is a mostly quiet whirlwind in an extremely fast tempo. The final variation, which follows without pause, possesses a bacchanalian abandon. A final reprise of the theme, again a reference to Prokofiev’s form, brings the symphony to a close.

The work was completed in Baltimore, Maryland on February 3, 2011. Lasting about twenty-five minutes, it is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones, tuba, two harps, timpani, percussion (three players), and strings. It is dedicated to my high school music teacher, John Merrill; without his kindness and encouragement I might never have found the fortitude to persevere in my dream of being a composer.”

Symphony No. 4 –

“The question of what music can “communicate” has been much debated.

It is the most abstract of the arts — e.g., what does a C-sharp “mean”? — and yet it clearly seems to have the capacity to speak volumes to the listener about the myriad aspects of life. Of course, Stravinsky opined that music was incapable of saying anything at all, that the “meaning” was supplied by the listener rather than by the music itself.

Ultimately this is a debate for aestheticians, not composers. But I do fervently believe that there is a “lingua franca” of musical expression, one that most composers have understood over the years and have employed to convey specific emotional states. Of course, some composers have gone even further, attempting to tell actual stories or to describe events in sound. This so-called “program music” can be quite detailed (Strauss’ “Ein Heldenleben”) or more vague (Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony). Sometimes composers have had a great deal to say about their expressive intent in a given musical work; at other times they’ve had little if anything to say. Asked whether listeners would devise the programmatic meaning of his “Pathetique” Symphony, Tchaikovsky famously replied, “Let them guess.”

For those of my scores in which I have had a reasonably specific expressive intent, I have usually tried to be open about the nature of that intent. However, there have been a few occasions when I have felt the need to say very little in this regard. The above paragraphs are preamble to the fact that, while I did have a particular meaning in mind when composing my Symphony No. 4, I prefer to keep it to myself. Some listeners may find the piece baffling but will nonetheless have to guess.

Composed for the New York Philharmonic and completed in Baltimore on June 30, 2013, this two-movement, twenty-minute symphony is scored for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, English horn, two clarinets, contrabass clarinet, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, four trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (three players), harp, celesta, and strings.”

Prospero’s Rooms –

In the days when I would have still contemplated composing an opera, my preferred source was Edgar Allan Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death”. A marvelous story full of both symbolism and terror, it is only five pages long and would thus require “padding” instead of the usual brutal cutting of the story. I had contemplated some sort of melding of the Poe story with Leonid Andreyev’s symbolist play The Black Maskers. However, I shall not be composing an opera, and so I decided to redirect my ideas into what might be considered an overture to an unwritten opera.

The story concerns a vain Prince, Prospero, who summons his friends to his palace and locks them in so that they will remain safe from the Red Death, a plague that is ravaging the countryside. He commands that there be a ball—the “masque”—but that no one is to wear red. But of course a figure clad all in red does appear; it is the red death, and it claims the lives of all in the castle.

Central to the story is the castle’s series of seven conjoined rooms, each furnished entirely in a single color and with a Gothic stained glass window of the same color. First is the blue room, followed by the purple, the green, the orange, the white, and the violet rooms. Last, buried in the deepest recess of the castle, is the black room. Only here is the window of a different color—it is crimson red. In the corner is an enormous ebony clock whose mournful tone so disquiets the visitors that they freeze, terrified, whenever it tolls. It is in this room, of course, that Prince Prospero meets his end at the hands of the Red Death.

Prospero’s Rooms is only intermittently programmatic. The opening music is intended to “set the scene”. The centerpiece is the middle section, an allegro that explores the rooms in the order presented by Poe. Rather than attempt to describe the rooms, I have tried to depict the actual colors themselves. The music slows again with the arrival of the seventh room and this point becomes more explicitly narrative in nature.

Perhaps the most specifically programmatic element of the piece is the sound of the ebony clock, which is heard throughout the work and which introduces each room as we enter it.

Prospero’s Rooms is dedicated to Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic.

Rouse’s music is difficult for me to describe but there’s always rhyme and reason (for the most part) in his compositions. I liked every work on this new recording and I suppose one possible reason for my enjoyment stems from the fact that the music hit me on an emotional level immediately. The music’s language, which is predominantly tonal (though the idea of tonality in Rouse’s hands is sometimes stretched to its limit), just found a way under my skin. Make no mistake, this is some intense music, perhaps even, at various points, barbaric in it’s means of expression and pounding a point across to listener, but I suppose that’s another reason why I’m attracted to it, but then there’s an unmistakable lyricism that comes out from the shadows from time to time that leaves one breathless and yearning for more. I’d say there’s almost this Mahlerian quality in the music as it plays on these two extremes rather well, but not in a kitschy way like a composer such as Kancheli has done.

If you’re already a fan of Rouse, then this is a mandatory purchase, but if you’re just coming to Rouse’s music, this could very well act as an introduction to the composer. Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic must be commended for their performances here. This disc is on my ‘Best of 2016’ list already and I do hope more people hear this music. Highly recommended!